New Media Museums Proceedings, 2022

Dead Artworks as Narrators: (Re)use of Broken Artworks in the Media Art Narrative at the Exhibition //Reincarnation of Media Art// in WRO Art Center in Wrocław (2019)

Table of Contents

Introduction

In order to reap as much benefit from works of art as possible, the perspective on their preservation might shift from thinking about prolonging life – to ‘being until death’. The quoted thought is the conclusion of one of the Getty Conservation Institute expert panels on changes and developments in the field of contemporary art conservation (2008).1) This paper provides commentary and analysis on 'dead artworks’, although the research is limited to media art, which, despite its youth, often dies first. The topic is touched upon in the exemplary exhibition exhibition Reincarnation of Media Art curated by Agnieszka Kubicka-Dzieduszycka in WRO Art Center in Wrocław (2019)2) – a Polish iteration of the concept of Mausoleum of Media Art realized at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM) by the Japanese artist group exonemo.3)

The following pages provide an overview of the current debate on the death of modern artworks, including media art. Then, in the context of various conservation approaches and artistic paradigms, forms of its preservation will be briefly mentioned, as well as sources of broken artworks. A contemporary critical view of forced preservation, excessive archiving and large quantities of artifacts in storage will be presented using a conservationist research perspective. The next section shows how to use broken artworks in the narrative of media art history. The final section includes research on attempts to systematize and name the objects discussed in the article.

Death debate

Fig. 1. Reincarnation of Media Art exhibition in YCAM Japan.

The 20th century was characterized by new paradigms, and significant changes in the field of art that have affected not only art audiences, but also critics, curators and conservators. Art preservation is complicated, so defining art, as well as deciding what to preserve and at what price, are difficult. Modern art is rapidly degrading due to fragile elements, experimental techniques and unstable new materials. As a result, we often encounter dead artworks that are the result of experimentation, that were damaged in transit or are mechanically damaged. Richard Rinehart lists three ways art dies in the context of media art: death by technology, death by institution, and death by law.4) Maintaining media artworks that rely on outdated technical devices is becoming increasingly difficult as specific models, their replacements, and experts in the technology vanish.

Curators and conservators, along with experts from a variety of scientific specialties, face challenges in acquiring and preserving electronic and digital works. Art conservation theory is evolving to adapt to the problems of newer technologies, which Pip Laurenson describes as a dynamic system, “a set of components, linked together in an organized fashion.”5) She stresses that keeping media art in use is the best preventive strategy. According to Hanna B. Hölling, these artworks, complicated by their media temporality, have the potential to be preserved through “emulation, migration and reinterpretation.”6). The identity of media art is scattered across different objects, processes and contexts, and the death of art becomes a topic of debate due to the potential volatility of media. This variability is strongly intertwined with the extensive documentation of the work, which in some cases becomes part of the artwork.7)

Art conservators discuss the death of art, but in the context of its avoidance rather than acceptance. The topic of art mortality was presented at a conference on contemporary art restoration Mortality Immortality? (1998),8) then at another organized by the Getty Conservation Institute (2008).9), and at a recent INCCA panel entitled Death of an Artwork (2022)10) Rosario Llamas-Pacheco recently summed up the issue by equating the death of art with its disappearance, even though the causes of art death vary from natural degradation to accident to intentional artistic action.11) Following Mario Sousa's paradigm of death, Llamas-Pacheco proposes an attitude of accepting the death of a work not only of its matter, but also of its concept.12) Regardless of the causes of death, collections have to deal with damaged works of art, their broken or replaced parts, which do not constitute a work of art, but are replaceable elements.

Despite preventive conservation, works of art lose parts, have their mechanisms replaced, and sometimes lose their meaning. As in the case of Joseph Beuys, whose Felt Suit (1970) is suspended in conceptual and physical limbo in the Tate Collection after being eaten by moths.13). Another example, Nam June Paik's works illustrate well the notion of interchangeable parts, and at the same time closely link art with rapidly aging technology, as seen in the review TV Garden (1974).14). Assuming the artist's awareness, the best precautionary plan, and tracking the technology adoption curve, we must take into account that some technical elements will break down and need to be replaced - but what about the originals?

Reincarnation of Media Art

The original concept for the Mausoleum of Media Art came from artist Kensuke Sembo, during a discussion on media art conservation between the exonemo group and YCAM curators. He and Masaki Fujihata invited artists to “consider the death of artworks and the possibility of their reincarnation in the future.”15) Visitors to the exhibition explored relics and documentation of time-based art in a mausoleum inside YCAM's main building. Audioguide was used to guide visitors through the exhibition, which began with a presentation of Nam June Paik's “death of the work” of CRT monitors from Video Chandelier No.1 (1989).

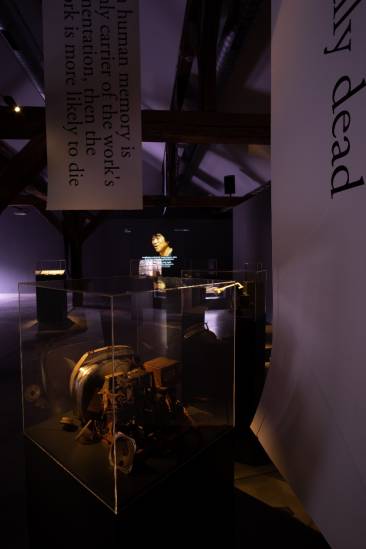

Fig. 2. Reincarnation of Media Art exhibition in Wro Art Center in Wrocław. Photo: Zbigniew Kupisz. Courtesy of WRO Art Center.

The Polish iteration of Reincarnation of Media Art was created as part of the 18th WRO Media Art Biennale at the WRO Art Center (2019), a pioneering festival and institution in Poland that has been promoting, producing and documenting media art for 30 years. The exhibition was curated by Agnieszka Kubicka-Dzieduszycka, and the works presented were selected in collaboration with other members of the WRO team. In this case, a synthetic voice led visitors through the mausoleum, referring only to the tomb with the entrance (Fig. 2), and told about the causes of death of the works displayed in the crypts - plexiglass cubes on pedestals (Fig. 3). The audio guide was played on old portable devices like a cassette radio or portable CD player.

Fig. 3. Reincarnation of Media Art exhibition in WRO Art Center in Wrocław. Photo: Zbigniew Kupisz. Courtesy of WRO Art Center.

Fig. 4. Reincarnation of Media Art exhibition in WRO Art Center in Wrocław. Photo: Zbigniew Kupisz. Courtesy of WRO Art Center.

The WRO Art Center showed dead works by eight artists collaborating with WRO and YCAM, including a recurring homage to the “father of media art”: the Wrocław exhibition also began with Nam June Paik, exhibiting the interiors of a broken CRT monitor from Zen for TV (1963), and a U-Matic cassette (1980s). This was followed by works by other artists: a cell phone used in Rafael Lozano-Hemmer's performance Hemmer Amodal Suspension (2003); a hard drive with data from Web Hopper (1996) by Koichiro Eto; YMO Techno Badge (1980) by Masaki Fujihata; old iPhones with apps by Nao Tokui (2008); VHS tapes from the performance Ucieleśnianie [Embodyiment] (1994) by Piotr Wyrzykowski; VHS with Performans na żądanie [Performance on Request] (2001) by Anna Plotnicka and Pawel Janicki; broken game consoles of the Gameboyzz Orchestra project (2001); broken floppy disks by Lukasz Szalankiewicz aka Zenial and the artist's audio release on floppy disk (1996-2019).

The exhibition in Wrocław was an example of various conservation strategies or relics of dead artworks. Preservation through documentation, which was developed to preserve time-based art, can be applied to Lozano-Hemmer, Plotnicka and Janicki. The light show photo album additionally focuses on viewers' memories. Works of art are also represented by technology, such as telephones, placing them in a historical context. The VHS tapes on display can be viewed as documentation - a record of Płotnicka's performance (2001), but also as an artifact used by Wyrzykowski in a creative act (1994). As Sylwia Szykowna notes, another layer of meaning is object memory, where the objects are tangible intermediaries between historical events. 16) Broken hard drives or floppy disks (Koichiro Eto) can also be used as a form of mediation. Nam June Paik's TV, on the other hand, best exemplifies the most important aspect of media art: variability and its implications for conservation strategies.

This conservation paradigm constructed by the Variable Media Network refers to practices aimed at maintaining certain parameters of the work's stability, transforming works of art, but in accordance with the intent of their creator.17) Another approach is “changeability,” a concept introduced by Hölling that refers to the possibility of changing one work of art into another, transforming conservation into the continuation of art.18) Being part of a work of art, Nam June Paik's TV carries at least one ruin-relic value mentioned by Llamas-Pacheco that deserves preservation: cultural, intentional, historical or iconic type.19) In addition, the artist's signature on the TV with the number 4/12 is reminiscent of Duchamp's gesture and designates a work that is one of a kind.20)

Reincarnation of Media Art also included an artist survey about the future of their work. Its results, as well as artists' awareness of the preservation of their works, are of particular interest to conservators. This awareness is a topic for a separate study, but it should be mentioned in light of the presence of Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, who promotes Best Practices for Conservation of Media Art from an Artist's Perspective.21)

To summarize the surveys realized as part of the Japanese exhibition: YCAM received 41 responses to a total of 124 surveys, four of which were made public on the project website. Masaki Fujihata responded to Kensuke Sembo's proposal to create an exhibition that looked like an ancient burial in the following way: “Who on earth would want to participate in such an exhibition? […] I don't want to see my works in a tomb.”22) Fujihata was eventually convinced, and several other artists provided responses ranging from a complete rejection of the work's materiality (Kyle McDonald) to meticulous planning and documentation of the work (Akos Maroy). Yap Sau Bin wrote about re-mediation - a type of conservation - in the sense of “analog→ digital→ analog,”23) which corresponds with Jussi Parikka's Media Archaeology.24).

For the Polish iteration, video interviews with the exhibiting artists were recorded and screened at the WRO Art Centre and on its online platforms. Among the videos and quotes, one slogan stood out: “A dead work is a forgotten work,” according to Zenial; so artists do not want to be forgotten. It should be added that media artists are among the most technologically aware creators, observing new, rapidly changing technologies. To conclude, the Reincarnation of Media Art project not only presented different approaches to preservation, but also artists' attitudes and raised awareness of conservation, not forgetting Nam June Paik's reflection “My TV is not always interesting, but not always uninteresting.”25)

Dead artworks

The purpose of this article was to assess the value of the objects displayed in the exhibition Reincarnation of Media Art. The most common noun used to describe the exhibited objects was “dead artworks,” as the founders of the mausoleum used the concept of death. In an examination of the Wrocław show, Szykowna refers to the exhibits as “relics” and “material remains.”26) Kensuke Sembo, one of the authors of the Japanese proposal, used the more direct term “corpses.” The term 'ruin-relic' is also defined by Llamas-Pacheco as: “the state in which the artwork, after the passage of time, […] has reached a point at which it is no longer capable of facilitating the entity’s experimentation.”27).

Therefore, objects should be preserved despite their poor condition or loss of integrity, because they reflect other cultural values and serve as witnesses to history. If one accepts Janina Hoth's definition, such witnesses could be the photographs of the performances presented at the exhibition Reincarnation of Media Art. She characterizes the dominant witnesses of historical knowledge, even though they are merely “mediators of a specific point of view.”28) These documents, according to Hoth, cannot be recorded in their current form because of their mediality, but should be re-edited by conservators/archivists and observers.29)

In this context, the greatest challenge comes from the readymade and the Fluxus movement, in which a document or its copy becomes a work of art, as Filipovic describes using the example of Marcel Duchamp's notes.30) As a result, it is difficult to have a clear definition of art documentation that could be useful in determining the status of an object. As Aga Wielocha points out, when Fluxus expanded the field of art to include happenings, actions and events, “the distinction between artwork and documentation began to blur.”31)

Actions and performances leave behind material traces in the form of documentation, as well as material artifacts and inanimate actors that are archived and displayed in exhibitions. These objects are crucial to the preservation of performance art because they are unused and inactive, but are preserved for their aesthetic and sculptural value.“32) When an artist modifies a display device to the point where it becomes a sculptural work, as Laurenson notes, “its significance conforms more readily to that of a traditional museum object.”33).

In an interview about dead artworks in the Tate collection, Patricia Falcão describes such things as 'dedicated equipment' and notes that the conservation path would be different in such a case, led by the sculpture conservation department.34) As a result, such “archived objects” are stored and monitored in a controlled environment alongside the rest of the collection, similar to the storage of Felt Suit, where an excavated archaeological relic retains the essence of its raison d'être, but no longer functions as such.”35)

Wielocha proposes that artifacts, i.e., the actual components of works of art, can be considered as documentation of artistic practice.36) The 'archival turn' was already postulated by Hölling, when analyzing media art, she suggested that an artwork could become an archive of itself.37) If we accept all physical changes in material works, every trace of time will be the subject of future inquiry, so instead of exposing the patina, we should do the opposite, Rinehart recommended.38) However, preserving each piece is difficult due to storage limitations and environmental sustainability.

In the case of media art, which typically contains electronic, partially replaceable elements, this method can be a challenge. Similar objections are raised by Hoth, who questions the desirability of preserving relics, asking whether an artificial market for relics does not work against the artist.39) One of the arguments for preserving such a collection is that it is actively used. Annet Dekker defines a digital archive as its “reuse instead of storage, circulation rather than centrally organized memory,” and uses “artifacts” to describe both objects and documentation.40) She adds in the essay that the archive allows for fresh interpretations of art, thus preserving the memory and life of the artwork.41)

Conclusion

Works of art have been constantly reinterpreted and transformed throughout history. This variability is particularly evident in media artifacts and has implications for the alternative modes of conservation discussed in the article and observed in the exhibition under study. The broken artworks on pedestals were retrieved from private archives and institutional warehouses, among others. Thus, Reincarnation of Media Art curated by Kubicka-Dzieduszycka and the WRO Art Center team, exemplified the active, generative management of the archive described by Dekker.42)

Art objects used as new methods of documentation can create “a different process of knowing knowledge.”43) Barker and Bracker emphasize the need to demonstrate the possibility that inanimate objects continue to resonate in museums or collections after their death.44) Returning to the idea in the article's title, the Reincarnation of Media Art example illustrates that the use of dead artworks as narrators of media art history extends the life of art and supports its preservation.