This is an old revision of the document!

Versions, fragmented works, or inaccessible artworks? Conservation approaches to Media Art Installations and Net Art Works in the collection of the C³ Centre for Culture and Communication Foundation

Introduction

The C³ Centre for Culture and Communication Foundation is a small Hungarian NGO, with a huge history and archive. Among its original aims in the late nineties was the introduction and expansion of scientific-technological innovations, alongside the fostering of meetings and cooperation among spheres of art, science and technology. The first publicly accessible internet hotspot in Hungary was set up in an exhibition organised by C³ in 1996. The C³ collection was created almost organically, accumulating works and content connected to its activities. Its organisation and preservation however have been a discussion topic for many years, if not decades. The catalog.C3.hu platform acts as a main interface for the collection, but the lack of resources means that maintenance work is undertaken only sporadically. Artist and researcher Márta Czene calls for the integration of media artists’ full bodies of works on the platform, related to the deficient documentation of László László Révész’s works. She also argues that documentation, while peers are alive, is crucial, similarly to the aims of Home Page, a new net art piece by Márk Fridvalszki and Anna Tudos, developed in 2022. This alternative net art archive which is a net art piece in itself aims to create a network of care by recalling the lost techno-optimistic view of the Internet and re-organising works from the collection in a new conceptual framework.

The formation of the C³ collection

The launch of the center in 1996 in Budapest was a result of careful negotiations with the Soros Foundation Hungary, Silicon Graphics Hungary and MATÁV (the Hungarian Telecom), them being the main funders. C³ can be perceived as the successor of the Soros Centre of Contemporary Art (SCCA) in Budapest, the largest in the region. The SCCA network was established in 1991 as an international NGO, and expanded to another eighteen countries previously part of the Soviet Block throughout the 1990s. The Budapest center evolved from the Soros Foundation Fine Arts Documentation Center, which operated from 1985 to 1991. With the end of the centralised system, the initial period of liberalisation created a structural crisis and drastic underfunding of the cultural sector. At the same time as the existing sources of funding were being withdrawn, there was a realisation that a grassroots system was needed, rather than a centrally managed one.1)) Linked to this realisation, the network's mission was to help the new system emerge and stabilise, in line with the principle that, in creating an open society, art can be a force for shaping society by challenging existing norms.2)

Over the next few years, 18 affiliated institutions were opened in various European countries, modeled on the Hungarian affiliate. Operating with a new type of art management, the institutions' manual of procedures aimed at generating international exchanges, encouraging the creation of new media works (through a major exhibition and scholarships each year) and documenting Eastern European art and integrating it into the global canon.3))

The Hungarian member institution was of particular importance and by the mid-1990s had established a dominant position in the scene, creating a new elite (curators, artists, critics) through the scholarship programme and its exhibitions. Majow shows before the 1996 foundation of C³ include SVB VOCE (1991) Polyphony (1993), Butterfly Effect (1996), and after: Perspective (1999), Media Model (2000), Vision (2002) – all in the Kunsthalle, Budapest, except Polyphony, which is considered as the first major public art event in the region. It’s worth mentioning the international conferences hosted by the SCCA Budapest as well, such as The Media Are With Us! (1990), Problem Video in 1991, and the VI International Vilém Flusser Symposium & Event Series in 1997. Works, footage and documentation from these events form the core of the collection of C³.

Internet hub at the Butterfly Effect exhibition, 1996, Kunsthalle Budapest

The SCCA network was put on a new structural footing following the restructuring of the funding scheme received from the Soros Foundation around 1996, and this is when the C³ Centre for Culture and Communication was established as a three-year pilot programme.4) Around the same time, all individual SCCA institutions became autonomous. In 1999 and 2000, a newly established but short-lived Amsterdam-based organisation, i_CAN, kept the former member institutions together with C³ as a founding member.

C³ and the world wide web

The main task for C³ after 1996, was to create public awareness about an emerging phenomena: the Internet.

“In the 90s, it was difficult to get online. Some universities would have an internet connection but on an experimental level. The technicalities (available modem, phone line) of it as well as the price put people off, but also nobody knew what it was, how it could be used. The first publicly available Internet hotspots in Hungary were set up for the exhibition Butterfly Effect in early 1996 at Kunsthalle Budapest, by C³ Foundation. There were 5 computers available and they puzzled the public. There were similar machines set up at the Internet Galaxy events, and Artpool had access, but they operated from a flat back then. At C³ eventually, there was an internet lab, with a free service: you had to register, drop-off visits were limited in time but that was also possible. There was even someone who assisted people while using the Internet on one of the 10 machines. After that, Internet Cafés were popping up, but there you had to pay.”5)

C³’s lab was free and open to the public, however, they had to offer assistance and courses to help people really grasp the potential of the web. The computers by Silicon Graphics attracted a young artist crowd too, as these were really cutting-edge machines at the time. A small but active community of artists worked there on various projects during that time. It was an active hub with a residency program, public events and exhibitions, web terminals, a library and a growing collection. The first public e-mail service was developed at C³ (freemail) and they had a project in which they encouraged NGO’s get online by distributing free domains to them. ventured into various collaborations, including the Pararadio net-based radio station (1997-2007).6)

The original aims of C³ included supporting the artistic production of new media artworks, running a residency and organising events, exhibitions. The regular, big-scale exhibitions, mostly international group shows of media art successfully blended local artists’ work with emerging, new directions in contemporary art. As the successor of the SCCA, the Soros Center for Contemporary Art, documentation has always been at the core of the aims of the foundation too. Most of the collection was built this way, through the initial residency program (1996-2002) and the annual exhibitions, between the late nineties and early 2000s.

The organisation was mentioned on the same page as Ars Electronica in Linz, or V2 in Rotterdam and established itself as a regional center for media art in a miraculously short amount of time. Through an international residency program focused on web-based projects among others, artists such as JoDi, Alexei Shulgin, Olia Lialina - spent some time in Budapest and created works that are now regarded as key works. By showing Hungarian artists together with more established names in their exhibitions, they accelerated their careers and helped them make use of possibilities abroad.

In 1999, the center became independent, and continued operation as a non-profit NGO, a foundation. The director of C³ since April 1997 is media theorist Miklós Peternák. With its 2005 move, C³ lost its own exhibition space and could no longer host public events. Labor Gallery in Képíró utca in Budapest acted as a satellite gallery, shared with the Sudio of Young Artists’ Association as well as the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts. Operating this way, there are fewer entries in the collection database from 2004 onwards, however, records are included until 2011.

Collection and catalog - conservation efforts until 2022

Currently, the collection is available in an online database and through the website of C³. These are both publicly available sites, and visitors can access a varying level of information on the artworks - in the case of some, the works are fully accessible (web projects, some video works). The catalog contains media artworks that have been realised with the collaboration of C³, online artworks, works produced within the framework of the C³ residency program and the Studio Grant as well as the documentation of media art projects realised by C³. Also featuring in the compilation are artworks produced by C³ which were presented to the public in larger exhibitions or in the C³ Gallery for which their internet appearance was not their primary medium. It also features recordings of public lectures, exhibition documentation (video), and other expanded content. The collection can be regarded as an archive, as there hasn’t been a new acquisition for many years now. Important to note, while the collection of C³ contains roughly 70 works by 40 artists, the catalog features over 700 works.

The catalog.C3.hu interface was created as part of the preservation project Gateway to Archives of Media Art (GAMA), in 2009. The EU project’s aim was ‘the establishment of a central platform to enable multilingual, facilitated and user-orientated access to a significant number of media art archives and their digitalised contents. The consortium comprised of a majority of the most important digital content holders for media art in Europe. The content provided constitutes approx. 55% of all media artworks presented online by European cultural archives and distributors. This amount will ensure a significant increase in use, re-use and cross-border visibility of the digital content when aggregated and accessible through one common interface.’7) The catalog was born, with organised data stored on a server that can be downloaded upon research or exhibition interest.

Screenshot of catalog.C3.hu, entry of the exhibition Poliphony (1993, Budapest locations)

However, with the digital acceleration post-2009, the common interface became outdated, the structure limiting, and the content forgotten-about. Sustainability factors weren’t highlighted enough in the original aims of the project, and the limited operation of C³ didn’t allow for the catalog to be activated, presented and regularly updated (with the exception of a 2012 accessibility update). Even the project website (gama-gateway.eu) that was supposed to work as a central access point ceased to exist. This process can’t be blamed on lack of expertise or skills as discussions on preserving media art have been happening since the birth of media art, also on the European scene. C³ previously took part in another initiative, ‘404 Object Not Found. What remains of media art?’ in 2003, which was a research project concentrated on various case studies focusing on concrete works to examine the problems and issues involved in the presentation, documentation and preservation of media art. There was a congress held in Dortmund at hartware medien kunst verein that concluded the project and where case studies were presented. C³ presented a case study related to the possible preservation of the online VRML artwork Cryptogram.8)

In 2008, as a unique collaborative effort, Elzbieta Wysocka conservator took on the enormous task of restoring9) Olia Lialina’s early net art work, Agatha Appears.10) For many years after that, the question: What will remain of media art? was especially in the foreground in Budapest, as the MAPS (Media Art Preservation Symposium) has been organised there by Ludwig Museum in 2015, 2017 and 2020. The event brought together global experts, and C³ director Miklós Peternák presented on many occasions. Another Ludwig Museum Budapest event, the exhibition titled Dead Web saw the S.O.S. restoration of a work by János Sugár, Dokumentum-modell, from 1997.11)

Taking all this experience into consideration, for the New Media Museums project, C³ decided not to focus on one case study. This is largely due to the rarity of occasions when they can reflect back on this collection, as it would have been very difficult to pick one work while there are bigger, more structural problems to bring up and solve. So, first of all, the database needed to be reinvestigated, with the help of the person who was responsible for its creation in 2008 and the 2012 update. As it became visible in this process, it is very important to be consistent with people when it comes to caring for older digital archives, whenever it’s possible. A lot of answers were found and a lot more questions were raised. Some structural problems are organisational, such as the catalog platform and collection on C³ website not correlating, some are communicational (user interface is outdated, the design is not responsive, images are very small), some are more serious (missing entries, uncomplete lists of works). This conversation resulted in some changes to the admin interface, which for example didn’t have a ‘search’ function before.

From these issues, an apparent deficiency was urging us to act: the oeuvre of László László Révész, who suddenly passed away in 2021 was represented in the archive but his entries were fragmented and incomplete. A frequent collaborator of C³, Révész was an artist who created a vast amount of work, integrating genres computer art, videos and installations. With the help of artist and reseacher Márta Czene, C³ could reconsider the way he is represented in the catalog.

The decicion was also made to look at the net-based artworks in the collection more closely and identify a need for better organisation and communication. The chosen methodology was to approach the collection from an artistic research point of view and explore the web-projects as one big category, instead of singling out works. This process was led by curator Anna Tüdős and artist Márk Fridvalszki.

These three strands: identifying structural issues and performing quick fixes, using the case study of one artist to test out the possibilities offered by the decade-old catalog platform, and artistic research concerning the preservation of the net art collection constituted C³’s conservation activities, for the first time in 2021 since many years.

Home Page - an investigation into preserving the net art collection of C³ Foundation

Why net art?

The C³ collection contains a small but significant selection of net-based works from the initial stages of internet art in Hungary and around. Most of these works originate from the second half of the 1990’s, an era characterized by the exploration of the web as a new platform and communicational tool. For artists of that time, websites offered a new media for experimentation, as structure and design principles were not written in stone yet. The artistic freedom to shape the internet motivated many creators to produce exciting and unique work. The C³ collection offers a selection of works, including dominant artists of this exciting period as well as local experiments. However, the preservation efforts are rather passive, the lack of resources don’t allow for the activation of individual works.

Over the years, many platforms and solutions have become outdated an unavailable, with some unique examples of preservation efforts that I will detail later. It is not easy to care for net art works for any institution. In 2022, with renewed interest in the 1990’s, and as a backdrop to the accelerating digital content-production, net art, and the artistic values it represents is again in the center of attention. Conversations around net art have been stimulated by many theoreticians and organisations for decades (such as the Variable Media Network, Monoskop or the Zentrum für Netzkunst) and conservation work on web-based artworks is undertaken in diverse parts of the world (Rhizome, LIMA) but it’s not common in the Central-Eastern-Europe region, which was a motivating force behind the recent Home Page project by C³.

We can’t go by the discussions regarding the terminology of net art, where a single dot or dash has major importance in terms of practices the term describes. Literature distinguishes between the versions ‘net art’ with space and ‘net.art’ with a dot, the latter stemming from Vuk Cosic, denoting the internet activist movement of the same name in the mid-90s, with members including Alexei Shulgin & Natalie Bookchin. Therefore, “net.art” is used in the literature as well as on the Home Page website specifically in relation to that movement, while ‘net art’ is understood as a much broader category, covering a wide range of internet-based arts practices.12) On the various platforms of C³, a variety of terms is being used to cathegorise works, including ‘net-art’, ‘web-based art’, ‘networked art’, and ‘web project’. Web project usually refers to works that are more process-based, and have an ever-changing nature, however at C³ the term is used as an umbrella term for net art. As the collection is currently available on different online platforms (websites), preservation efforts have identified the need for an overarching, synthetic summary or presentation that integrates the interdisciplinary nature of the works in the collection.

For this process, a loose methodology os artistic research was applied.

Net art works and artists at C³

Screenshot of Home Page (www.homepage.C3.hu) featuring Alexei Shulgin’s From

The net art collection was set up in line with the original aims of C³: to promote and explore the possibilities of the Internet for wide audiences. We can set up three cathegories of net art works in the collection: 1) works that were created in the framework of the international residency program, 2) works that were created by visiting local artists and 3) websites, that were not made with artistic intentions, but have preserved some artistic value (this cathegory includes websites created for exhibition documentation, conferences, radio stations or video collections, etc.). As with the most of early net art works, their interdisciplinary nature makes them difficult to cathegorise. While Alexei Shulgin’s ‘Form’13) from 1997 is the perfect manifestation of a classic net art piece, the same can’t be said about the work of Dutch-Belgian artist duo Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans (JoDi), ‘Ctrl-Space’ from 1999. This can be found under web projects on the C³ website, however in reality, it is not a net art piece, but a downloadable file that was then uploaded to a game called Quake (a software) to create a custom game environment. Ctrl-space is described as a network game available from and playable on the Internet, but the definition of network game has changed significantly and means something completely different since 1999. Another example of an interdisciplinary net art piece is ‘Lapsus Memoriae’ by urtica (Violeta Vojvodic + Eduard Balaz) from 2002, described as an Internet game, or online memory game.14)

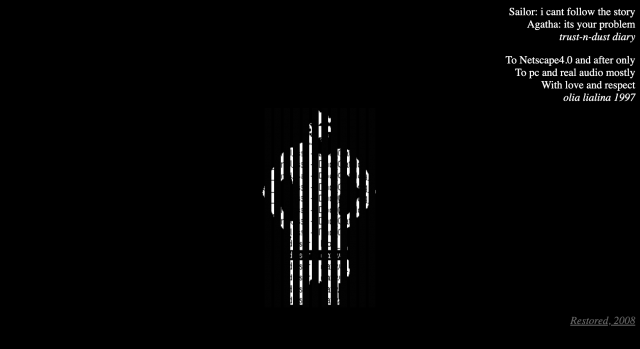

One of the iconic works in the collection is ‘Agatha Appears’ by Olia Lialina from 1997, which went through an extensive restoration process in 2008.15) Typical conservation issues became apparent by then, such as incompatibility with contemporary browsers, losing the interaction element, and corruption or loss of certain files. As many early websites, the home page provides instructions on how to view it, however those conditions can only be imitated in an emulated environment.

Screenshot of Agatha Appears

“To Netscape4.0 and after only

To pc and real audio mostly

With love and respect

olia lialina 1997”

The process initiated by conservator Elzbieta Wysocka set an example for the organisation but also demonstrated the necessary effort and expertise to treat the delicate works on a suitable level. For the 2020 exhibition at the Ludwig Museum Budapest, the work ‘Document Modell’ by János Sugár from 1997 was restored. Without any documentation of the original, the reconstruction was based on the faint memories of the artist, arguably creating a new work based on the old idea. Due to the technological updates of the original host's server, all media had to be replaced on the site, including videos of Budapest traffic security cameras from 1987, and incoming messages of the artist's answering machine from the early 1990’s among others. Interestingly, on the occasion of the same exhibition in 2020, Olia Lialina explained her decision not to allow the presentation of Agatha Appears by saying that the exhibition of the work requires the simulation of the original hardware and software interface, otherwise it is available online for anyone to see.

With time passing, and internet standards changing, more and more works become unaccessible. On the other hand, as the C³ collection demonstrates, accessibility is not enough for the preservation of an artwork. Without activation via presentation, discussions, establishing networks of care and disseminating knowledge, artworks become forgotten about. For the Home Page project, our aim was to save this snapshot of time when the web was regarded as an artistic medium, surrounded by endless enthusiasm and utopian optimism for the future. Instead of focusing on one work, we took the collection as a whole and analysed it looking for specificities in terms of unique language, theoretical charge, activist motivation and communication innovation. We wanted to create a new work where browsing is dominated by the joy of discovery as opposed to information carefully organised to be available by one click. The new artwork takes the form of a website, and identifies itself as an alternative archive. This doesn’t mean disregarding the conservation perspective, quite on the contrary - our aim was to offer an expanded view of conservation in practice and use the opportunity of the New Media Museum project to present the essence of the early works in C³’s care for a wider audience.

Home Page, an alternative net art archive

Mark Fridvalszki’s artworks deal with the sensual materiality of failed modernist visions. Usually the artist mixes a wide variety of media, such as wallpaper, found and manufactured objects, digital printing and other printing techniques and combines them in all-embracing collages. His artistic program can be described as archaeo-futurological, meaning that it deals with the remains of forgotten utopias, the cultural sediments of our lost collective future. He was commissioned by curator Anna Tudos, who was a colleague at C³ for 4 years and knew the collection well.

After identifying the main topic, Mark instantly drew a reference to Ferenc Kömlődi’s Cathedral of Light16), which became an inspiration and guide for creating the website. The goal from the start was to revive the visual aspects and logical structures of the net art works in the early 90s. The creators wanted to avoid nostalgic expropriation, and preserve and present the Zeitgeist of the 1990s in Hungary and Central-Eastern Europe by including visual inspiration and text from that time. At the same time, Home Page uses a retrofuturistic visuality of the 60s/70s, its design is geometric and the colours are vibrant. This work, similarly to Fridvalszki’s other works, is a collage, where the individual elements have a very important referential value.

The artist expressed that creating the website was more like editing a publication for him, and curatorial work helped to coordinate the organic integration of text and image. Featured text was chosen following the preliminary research, which consisted of conducting interviews, digging in the archives and consulting scholars.

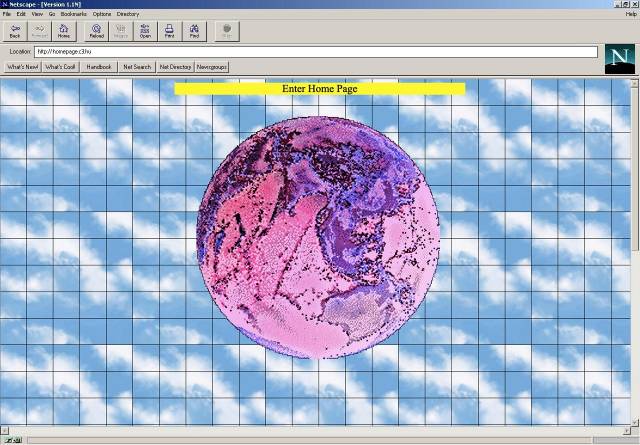

Screenshot of Home Page in Netscape, one of the most popular browsers of the 1990s. Graphics and concept by Márk Fridvalszki

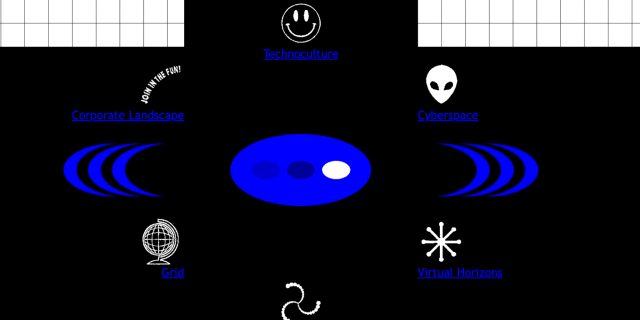

The site launches with a spinning globe, suggesting the Idea of the Internet as the connector of the world. These pre-pages were also common features of early websites, mostly featuring information or a simple ‘Enter’ button to give some time for the website in the background to load. After entering, visitors are faced with the main Menu. In structuring the menu items, the creators were careful to ensure that they were poetic but informative, that the topics were distinguishable even if they were related (e.g. there are links between the ‘Cyberspace’ and the ‘Grid’ sites, but their focus was noticeably different), and that the dual; local and universal references of the project worked well together. A good example of this is when a timeline is placed above a graph of the dot-com balloon, to give a sense of the interplay between the Hungarian and the larger context, and that Hungary was indeed relatively ahead in terms of internet access and net art.

Screenshot of Home Page (www.homepage.C3.hu)

Under ‘Technoculture’, an interdisciplinary understanding of the word is demonstrated:

The definition of technoculture goes beyond music, literature, film, video, visual arts and all other new forms of artistic expression. It describes the sense of a changed world(…).’17)

Under ‘Corporate Landscape’, the creators reflect on critical internet culture and flag up anti-consumerist attitudes, the societal distance and loneliness created by technology, but also the foundation of the historical milestones such as the dot-com bubble. Here, Ferenc Kömlődi’s words align with Geert Lovink’s vision of the Internet that can act as a self-generating tool to bring together critics, social movements, NGOs, and people.18)

The section ‘Cyberspace’ shows the twisted identities and realities created by the online environments and connects the then-new notion of cyberspace with a selection of artworks. Similarly, ‘Grid’ explores the drastically new way that information was organised via computers, online. Many artists took inspiration from the abstract, mathematical, simple yet informative grids that just started to define digital life in the 1990s. Works by Balázs Beöthy, Gyula Várnai and Hajnal Németh are placed alongside Alexei Shulgin’s. ‘Hyperdimension’ works almost as an audiovisual artwork on its own, with music composed by Elod Janky and a narrative scrolling structure evoking early net art artist strategies.

Last but not least, ‘Virtual Horizons’ contains the most local knowledge and archival data that can be useful for future researchers. In this section, the website details how the introduction of the World Wide Web actually worked in 1990s Hungary, why artists and students took on this medium and how some of the first few websites were designed. It details the history of the web more in detail, explaining how it could really be regarded as the most democratic medium.

Preservation approach

When it is not possible to update a database (of net art works), the right solution is not to create a new one, bypassing the problem. Software-based artworks are ever-changing, therefore their preservation needs to be flexible. Any presentation of them can be interpreted as a re-enactment, the original ideas at the core but never fully identical with the original. Some artists argue for the necessity of the original way of presentation in terms of software, hardware and physical environment (Olia Lialina), some others allow the work to transform with the time passed (Janos Sugar). The exhibition Seeing Double: Emulation in Theory and Practice in 2004 at the Solomon R. Guggeinheim Museum presented the results of these two schools side-by-side, pairing artworks in endangered mediums with their re-created doubles in newer mediums.19) In the case of Home Page, a new work was created based on the complex whole of the net art collection with the aim to bring new value into it. Home Page may not preserve the works in the net-art collection in the form in which they were once available, but rather fits into a new wave of preservation paradigms that sress the impotance of systematical presentation, the importance of curatorial decisions in order to preserve the essence of the works, and the inclusion of different actors and disciplines in the “network of care” of the works.

The post-custodian paradigm calls for the recontextualisation of archives to seek knowledge and understanding rather than just documentation and control.20) In archives following this model, similarly to C³, ownership rights may not reside with the institution but rather with individuals. Archivists take on the role to organise records in relation to other records in the archive, or even in other archives elsewhere, working with others towards the same or similar goal, creating new records and contextualising content on the way. This is a clear shift from traditional archival practises when responsibility is more focused and power-relations are more fixed. This paradigm supposes dynamic borderlands within and between archives, creators, subjects, and users. Although it is usually connected to participatory archives models, in this case, it was useful to think about it in relation to the C³ catalog, and preservation efforts where instead of focusing on a single work, the focus was on mapping the dynamic heritage and context of the net art collection.21) Home Page follows the paradigm in its effort to present the recontextualized collection in the “larger historical and social landscape”22) surrounding them.

Home Page includes net art works, physical art, video art, a documentary, quotes, screenshots to contribute to the interpretation of the mindset, digital culture, utopian or sometimes apocalyptic visions of the nineties. That “Software is stuff unlike any other.” and that “Cyberspace is unlike any physical space.”.23) It was an important to add “broken artworks” on the site, such as Szilvia Seres’s Culture is Consumer Goods from 1999, which we have a description of, complete with screenshots, although the original files are lost. The inspiration came from Gallery 404, a website created to contest the term “the internet never forgets” and to present the early 90s net art generations “attempt to plant a cultural stake in cyberspace”24) via presenting broken artworks.

Future Prospects

The actual home page of C³, www.c3.hu, is a net art work by Balazs Beöthy, referencing the periodic table and the unity of science and art. It was developed in 1997 and has only seen minor changes since then, even those minor changes were documented on a special website.25) For many, it seems old and dusty, a relict from the past that needs an urgent upgrade. For some, it is however an imprint of a different time, when the belief in technological advancement was stronger, and the power of experimentation ruled over economic profit, and that’s why it is unlikely to ever change. The home page still has all the information, although it might be an unusual experience to navigate it.

Net art requires conservation practices that consider records (or artworks, in this case net art works) as a process, instead of fixed, as “an assemblage that can mutate over time and according to context”.26) On the other hand, many institutions or caretakers are unable to perform regular updates and transform together with the works. Experimental efforts, such as Home Page can offer a fresh look, start discussions and activate networks of care in such situations. Jon Ippolito once said in an interview27) that “almost every time when you preserve works of new media, it takes a lot of money, it takes a lot of effort. (..) But on the other hand, if you look at early games, they have been preserved not by museums, not by curators, not by conservators, but by game enthusiasts and no one gave them a huge grant. They are preserved because they have a fan base(…)”. If there are enough people enthusiastic about these works, or excitement can be generated around them, we get closer to being able to preserve them.

Flóra Barkóczi in her article28) uses Bourriaud’s term “dee-jaying” to describe the creative process resulting in Home Page, where the artist creates work by reorganising, or re-contextualising existing artistic practices.29) Presenting the fragments of early net art culture in context, almost using them as raw materials rather than archival relics, the result is a kind of remix, that poses questions realted to the heritage of this culture and makes connections to contemporary works. By presenting early traces of internet culture as changing raw material rather than archival relics, the result is a kind of “remix” that can raise new questions. Home Page remains an open platform with the possibility to expand. All aspiring DJs are welcome to do a new remix.

Interview: http://three.org/ippolito/writing/ippolito_verschooren_interview.html