New Media Museums Proceedings, 2022

Versions, Fragments or Inaccessible Works? Conservation Approaches to Media Art Installations and Net Art Works in the Collection of the C³ Centre for Culture and Communication Foundation

Introduction

The C³ Centre for Culture and Communication Foundation is a small, yet long-established NGO with a video archive and media arts collection. The Centre was founded in the late 1990s with the aim of showcasing scientific and technological innovation and promoting collaboration between art, science and technology. For example, one of the C³'s exhibitions featured Hungary's first publicly accessible internet hotspot. C³'s collection and archives have grown organically through the accumulation of works and content related to its activities.

The main interface for the collection is the catalog.C3.hu platform. Although preservation has been a matter of debate for years, if not decades, maintenance work on the platform is currently sporadic due to lack of resources. In this article, we present a new work called Home Page, an archive of net art selected from the C³ collection. The archive reorganises the works into a new conceptual framework, evoking the lost techno-optimist perspective of the internet. Its development was inspired by the idea of integrating the complete works of media artists on the platform and the importance of documenting art while the artist is present.

The formation of the C³ collection

The launch of the centre in Budapest in 1996 was the result of careful negotiations with the Soros Foundation Hungary, Silicon Graphics Hungary and MATÁV (Magyar Telekom), who provided main funding. C³ can be seen as the successor to the Soros Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA) in Budapest, the largest in the region.1) The SCCA network was established in 1991 as an international NGO and expanded to eighteen other former Soviet bloc countries throughout the 1990s. With the end of the centrally planned system, the initial period of liberalisation led to a structural crisis and drastic under-funding in the cultural sector. With funding sources being withdrawn, it was recognized that a bottom-up system was needed rather than a centrally managed one.2) Related to this realization, the network's mission was to help the new system emerge and stabilize, in line with the principle that art can be a force for social change by challenging existing norms in the creation of an open society.3) The affiliated institutions were modelled on the Hungarian branch. Operating with a new type of art management, the institutions' procedural manual provided guidelines for generating international exchanges, commissioning new works (through a major exhibition and grants annually), and documenting Eastern European art and integrating it into the global canon.4)

The SCCA network was put on a new footing around 1996, following the restructuring of the funding scheme by the Soros Foundation. At this point, the C³ Centre for Culture and Communication was created as a three-year pilot programme.5) At the same time, all the individual SCCA institutions became autonomous. In 1999 and 2000, a newly created but short-lived Amsterdam-based organisation, i_CAN, brought together the former member institutions, of which C³ was a founding member.

Fig. 1: Internet hub at the Butterfly Effect exhibition, Kunsthalle Budapest, 1996. Source: C3 Foundation.

SCCA Budapest and C³ have been of great importance both locally and internationally. Major exhibitions before the C³ was founded include SVB VOCE (1991) Polyphony (1993), Butterfly Effect (1996), and subsequently Perspective (1999), Media Model (2000), Vision (2002) - all at the Budapest Kunsthalle, except for Polyphony, which is considered the first major public art event in the region. It is also worth mentioning the international conferences organised by SCCA Budapest, such as The Media Are With Us! (1990), Problem Video (1991), and the VI International Vilém Flusser Symposium & Event Series (1997). Works, recordings and documentation from these events form the core of the C³ collection.

C³ and the world wide web

After 1996, C³'s main task was to raise public awareness of a new phenomenon: the internet.

“In the 90's it was difficult to get online. Some universities had Internet connections, but only on an experimental level. The technical details (availability of modems, phone lines) and the cost were a deterrent, but nobody knew what it was or how to use it. The first publicly available Internet hotspots in Hungary were created by the C³ Foundation in early 1996 for the exhibition Butterfly Effect in the Kunsthalle in Budapest. There, five computers were available and they puzzled the audience. Similar machines were also set up at Internet Galaxy events and Artpool had access, but at that time they were operated from flats. The C³ did eventually have an internet lab, with a free service. You had to register, drop-off visits were time-limited, but it was possible to do this. There was also someone to help people while they were surfing the internet on one of the 10 machines. After that, internet cafés appeared, but there you had to pay.”6)

The C³'s lab was free and open to the public, which was also provided with help and courses for navigating the web. Silicon Graphics computers, truly state-of-the-art machines at the time, attracted a small but active community of artists, which developed various projects. It was an active centre with a residency programme, public events and exhibitions, web terminals, a library and a growing collection. C³ also developed the first public e-mail service (freemail) in the country and helped NGOs to get online by sponsoring web domains. C³ ventured into various collaborations, including with the Pararadio net-based radio station (1997-2007).7)

C³'s original mission included supporting the artistic creation of new media art, running a residency and organising events and exhibitions. Regular, large-scale group exhibitions of mostly international media art combined the work of local artists with emerging new directions in contemporary art. As the successor to the Soros Centre for Contemporary Art, documentation has been at the heart of the foundation as well. Much of the collection was built up in this way, through the initial residency programme (1996-2002) and annual exhibitions between the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The organisation has been mentioned in the same breath as Ars Electronica in Linz and V2 in Rotterdam, and in a short time has become a regional centre for media art. Through an international residency programme that focused on web-based projects, among other things, artists such as JoDi, Alexei Shulgin and Olia Lialina, spent time in Budapest and produced works, many of which are now considered key. By showing Hungarian artists alongside more established names in their exhibitions, C³ has accelerated their careers at home and abroad.

In 1999 the Centre became independent and continued to operate as a non-profit foundation. The director of C³ since April 1997 has been media theorist Miklós Peternák. With the move in 2005, C³ lost its own exhibition space and could no longer host public events. The Labor Gallery in Képíró Street, served as a satellite gallery, shared with the Association of Young Artists and the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts. The database of collections has therefore fewer entries from 2004 onwards, but there are entries until 2011.

Collection and catalog: conservation efforts until 2022

The collection is currently available in an online database and via the C³ website. Both are publicly accessible sites and visitors can access different levels of information about the works - some works, especially web projects and video works, are fully operational and accessible. The catalogue includes media art works co-produced by C³, online works, works produced under the C³ residency programme and Studio Grant, and documentation of media art projects carried out by C³. It also includes C³-produced artworks that have been shown in major exhibitions or at the C³ Gallery and for which the primary medium was not the internet. It also includes recordings of lectures, video documentation of exhibition and other content. No new acquisitions have been made for many years. It is important to note that while the C³ collection counts roughly 70 works by 40 artists, the catalogue features over 700 works.

The catalog.C3.hu platform was created as part of the Gateway to Archives of Media Art (GAMA) preservation project in 2009. The aim of the EU project was “the establishment of a central platform to enable multilingual, facilitated and user-orientated access to a significant number of media art archives and their digitalised contents. The consortium comprised of a majority of the most important digital content holders for media art in Europe. The content provided constitutes approx. 55% of all media artworks presented online by European cultural archives and distributors.”8).

Fig. 2: Entry on the Polyphony exhibition (1993) on catalog.C3.hu. Source: C3 Foundation.

However, with the digital acceleration after 2009, the common platform has become obsolete, the structure restrictive and the content forgotten. Sustainability was not sufficiently addressed in the original objectives of the project and the limited operation of C³ did not allow the catalogue to be activated, presented and regularly updated (with the exception of an accessibility update in 2012). Even the project's website, which was supposed to be a central access point, eventually ceased to exist.9) This cannot be blamed on a lack of expertise or skills, as the debate on the preservation of media arts has been going on since the birth of media arts, including on the European scene. The C³ was previously involved in another initiative, 404 Object Not Found. What Remains of Media Art? (2003), which was a research project focusing on specific works, using different case studies, to investigate problems and issues related to the presentation, documentation and preservation of media art. The project concluded with a congress at the Hartware Medien Kunst Verein (HMKV) in Dortmund. C³ presented a case study on the possible preservation of the online VRML artwork Cryptogram.10)

In 2008, in a unique collaboration, conservator Elzbieta Wysocka took on the challenging task of restoring Olia Lialina's early net art work Agatha Appears (1997).11) For many years afterwards, the question of 'what remains of media art?' was particularly prominent in Budapest, where the Ludwig Museum hosted the Media Art Preservation Symposium (MAPS) in 2015, 2017, 2018 and 2020. The event was attended by international experts, including C³ Director Miklós Peternák. At another event at the Ludwig Museum in Budapest, the Dead Web exhibition, the public was able to see a restoration of a work by János Sugár entitled Dokumentum-modell (1997).12)

Taking all these experiences into account, C³ decided not to focus on a single case study for the New Media Museums project. This is largely due to the fact that there is rarely an opportunity to look back at this collection. It would have been very difficult to select a single work, while there are larger, structural problems to be addressed and resolved. So, first of all, the database had to be re-examined, with the help of the person who was responsible for its creation in 2008 and its update in 2012. As has become apparent in this process, it is very important to be consistent with people when looking after older digital archives. Many answers were given and many more questions were raised. Some of the structural problems are organisational, for example the catalogue platform and the collection on the C³ website do not correlate, some are communicational (the user interface is outdated, the design is not responsive, the images are very small), some are more serious (missing entries, incomplete art catalogues). This discussion has led to some changes in the administration interface, where for example there was no search function before.

From these problems, one obvious shortcoming urged us to act: although the oeuvre of László László Révész, who died suddenly in 2021, was represented in the archive, his entries were fragmentary and incomplete. A frequent contributor to C³, Révész was an artist who produced a large body of work, integrating the genres of computer art, video and installations. With the help of artist and researcher Márta Czene, C³ was able to rethink how it represented his work in the catalogue.

The decision was also made to take a closer look at the net-based artworks in the collection and improve organisation and communication. The chosen method was to approach the collection from an artistic research perspective, and to examine the web-based projects as one large category, rather than isolating individual works. This process was led by curator Anna Tüdős and artist Márk Fridvalszki.

Starting in 2021 for the first time in many years, C³'s preservation activities consisted of the following three strands: the identification of structural problems and their rapid resolution, the use of an artist case study to test the potential of the decade-old catalogue platform, and artistic research into the preservation of the net art collection.

Preserving the works of László László Révész

László László Révész studied painting at the Hungarian College of Fine Arts (‘Magyar Képzőművészeti Főiskola’) and animation at the Hungarian College of Applied Arts (‘Magyar Iparművészeti Főiskola’). He created dadaist, intellectual performances with András Böröcz in the 1980s. From 1990 on, painting and films became decisive in his art, however, he had already made art pieces on his computer since the 1980s and had also continuously exhibited works of video art and installations. Working at VOX Television in Cologne, Germany, and also later on in several scholarship programs, he could use most modern computers and sofwares for his artistic projects that were not accessible in Hungary. Besides appearing in numerous European and American intitutions, his art pieces were also shown at the 8th Documenta in Kassel.

Narrativity and parallel perception, montages of juxtaposed images like open windows on a computer screen or iconostases play a pivotal part in his art. His versatile work spanning more than four decades was ground to a halt by his sudden death in March last year.

Although he was a regular participant of almost all exhibitions, programs of the C3 Foundation or earlier the Soros Center for Contemporary Arts (SCCA),13) documentation regarding him is fragmented and partly unsystematic in the archives and collections of C3, moreover, which of his previously exhibited pieces, if any, could be reconstructed without the artist and at what standard, remains questionable.

In the following, we will use three examples to describe the shortcomings and pitfalls of the documentation methods in C3's archives, as well as those characteristic of Hungary in the 1990s with regard to new media art. Please note that Révész's oeuvre is only one example, he is not a better or worse documented artist than the average, it has only become relevant because his tragically sudden death closed the possibility of communication with him, making it impossible to answer any further, potentially crucial questions.

The Triumphal Arch (Diadalív)

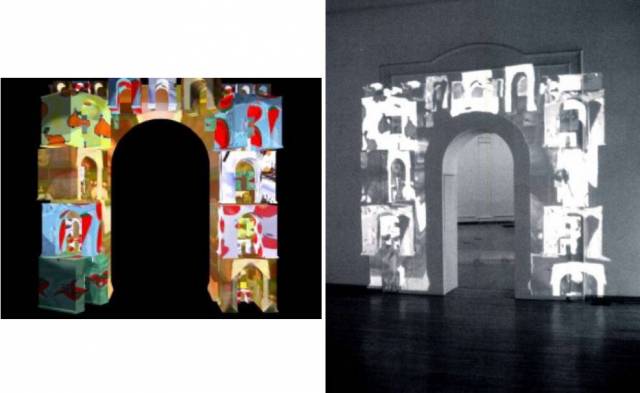

Fig. 3: Révész László László, The Triumphal Arch, 1996.14)

The first example is The Triumphal Arch, an art piece by Révész presented at the C3 exhibition called The Butterfly Effect (A Pillangó-hatás) in 1996. The exhibition was the first attempt to present contemporary media art in a historical context in Hungary. The material exhibited in the halls of the Art Gallery (Műcsarnok) comprised of two parts: Media relics (Médiarelikviák) showed Hungarian, Central and Eastern European discoveries of technology and media history, while Coordinates of the Present (Jelenkoordináták) displayed Hungarian and international works of media art.15)

Révész’s work of art presented here was a triumphal arch projection. The description in the catalogue does not depict the finished work of art, it could have presumably been the artist’s preliminary plan or concept about how he would exhibit the piece. It starts with a short technical description and then goes on to the interpretation, the cultural and political readings of his own work.

“A piece of canvas, measuring 2 x 2.20 meters and cut into the shape of a triumphal arch, is hung from the ceiling at a distance of one meter from the plane of the wall. The bottom edge of the canvas is at a height of 1.90 meters above the floor. A black, homogeneous form “complements” the arch on the wall; the video equipment, which is also hung from the ceiling, projects a computer animation over the arch, which corresponds, both in dimensions and in theme, to the “screen.” The recorded material, an approximately two-minute-long and continuously replayed loop, has morphic character and is presented in strong contrasts. The morph always begins with a 3D/CAD structural drawing of a triumphal arch. In the course of the brief (3-4 seconds) transformations and re-transformations, it is this structure that turns into mobile compositions which derive and originate from the associative domain of the ideas of abundance-glory-triumph. These characteristic compositions are primarily the products and fruits of Eastern (Central) Europe, most notably melons, apples, plums and their variations of form. Thus I also diverge from the antique - or pseudo-antique - triumphal arches in the sense that I create a seemingly arbitrary artwork, as opposed to propagandistic (and counter-propagandistic) art, in which I manipulate art's disburdenment of propaganda. In other words, I manipulate that stage of development in the life of Central and Eastern Europeans when the politicization of art - its propaganda - is no longer important, but the “new” keeps us waiting in every domain, or as in my case, emerges as a variant of old forms.”16)

Contrary to the description, the work that appeared at the exhibition was realized in a slightly different manner according to press photos, the documentation of both C3 and the Art Gallery.17) The piece of screening canvas emerging high in space and the black, three dimensional complementary form were omitted, instead, the screening was adjusted to the big door connecting two halls of the Art Gallery. Hence, the public could actually proceed under the arch itself. We suppose this form, much more simple and maybe more favourable than the one in the original plan, was inspired by the features of the place at the moment of directing.

In a sense, this piece had become an iconic part of the exhibition, almost all press articles, recommendations, summaries included a photo of it. Sadly, arts press articles do not abound in descriptions of the works of art either, they are mainly engaged with the then unusal topic of the exhibition and the fact itself that it could be realized.

The exhibition and the opening ceremony were documented by the Art Gallery on video, but the person in charge after video taping the opening speech, recorded the halls in succession at a swift walking speed, all in all devoting only about 10 seconds to this actual piece.18). C3 also stores videos about the exhibition, a part of which is publicly available with The Triumphal Arch being visible in a clip edited for the twentieth anniversary of C3.19) Six-eight different photos were taken of it and published,20) but all of these, just like the videos, only show the triumphal arch decorated with fruit varieties, and colleagues taking part in the exhibition cannot recall for sure either whether the space structure described by Révész was actually presented or not21). Based on the visual documentation, movement, the morphic character and rotation of the details cannot really be experienced either, because the same moment was randomly captured by almost all photographers. C3 does not possess the original files, and since probate hearings will not be closed in the foreseeable future, the heritage may not be researched. Let me note in brackets here that even if it was open for research, knowing László László Révész’s self-documentation and self-organization habits it would require tremendous efforts to locate the files, if it was possible at all.

It is unexpectedly fortunate though that in the years before his death the artist shared with me a YouTube channel of his own consisting of mostly private, disorganized and partly unlabelled videos so that we could write about his old films,22) It was in this collection of videos that we noticed an unlabelled, few-second-long moving image23) that basically matches the 1996-description of the work. It cannot be the original material that was projected, because on the basis of the preserved documentation the framing triumphal arch form appeared in front view there, however, it could obviously be some kind of a visual design that may have been exported from the original CAD file. This imagery features the initial, spatial structure of the triumphal arch, but no conclusions may be drawn from this as for the actual piece that was eventually exhibited.

Fig. 4, 5: Révész László László, Triumphal Arch, 1996.24)

SAN

In an artist’s life it happens quite often that a work of art created in a technically well-equipped environment, under ideal circumstances must be orchestrated for the more modest conditions of an exhibition. This may also cause numerous uncertainties during reconstruction if the artist does not differentiate the versions with subtitles or some kind of notation, and photos taken in the previous location, where he had presented them as the exhibition plan, are mixed in the exhibition documentation with the version appearing in the new exhibition.

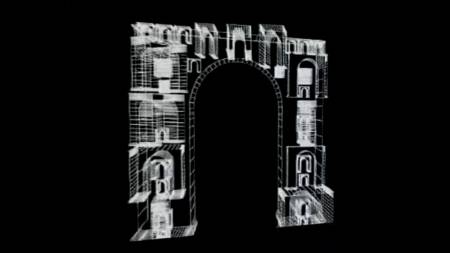

The case of László László Révész’s video and computer installation SAN, shown at the Media Model (Média Modell) exhibition organized by C3 in the Art Gallery in 2000, is an example of such a situation.25) 26)

Luckily, both the video material screened in the Art Gallery and the projected map that was used in the video installation were preserved after the exhibition, with the help of which the installation can be reconstructed even if the quality of the video leaves a lot to be desired.

The question that arises, also relevant for The Triumphal Arch, is what can be considered an original work of art in this case, that is in case of an installation for an exhibition. The piece designed by the artist and intended to be put on view on site, or the piece that was realized then and there as adjusted to the advantages and disadvantages of the site, financial resources or lack of infrastructure? Certainly, there are different versions, and there should be, since all sites are varied, and at best installations basically possess a kind of flexibility that makes them adaptable to a given exhibition hall. What exactly happened in this specific case, or whether the artist had a sense of lack in connection with this exhibition, we will never know.

In the documentation package of the Art Gallery’s library we found a letter about the Media Model exhibition from László László Révész to Miklós Peternák, the curator of the exhibition.27))

The artist asks for two projectors to display the work, for a six-minute videoloop on one and for the display of an interactive computer image on the other. He would like to see both in the same size, one projected under the other. He refers to a previous appearance of the work at an exhibition in Berlin also sending pictures of that. The pictures were not included in the documentation, but they are available at the C3 website where the works on display at the Media Model exhibition are documented28), designating the place where the work was created, and the exhibition where the pictures were taken. However, some other photo documentation made at the Media Model exhibition will not appear here.

Description of the work on the exhibition website:

“San the single channel video:

Shot with one take dolly in half circular movements using simple actions of couples facing each other.These couples are identified with the action they constantly repeat.The half circled choreography of the camera and the position of the couples creates a framing structure.The first couple facing south and north is closer to the camera framing the second couple facing east and west.When from this position the camera moves to east west there is a new north south couple and so on.

San the interactive:

is an explanation of San with the floor plan used for the shooting as the main interface. Moving in the space and hierarchy with a structured preconception while watching the space as a two dimensional representation of that space. An explanation of watching and understanding structures based on structures such as the structure of cards, floor plan.”

Fig. 6: Révész László László, SAN, 1997-1998. Exhibition in Berlin.29)

We are quoting the full text because of its complexity and obscurity. In one of the photos to illustrate it you can see a still image of the video described above, in the others a two dimensional map/floor plan turned into 3D, where stills of the video participants appearing as couples were inserted in designated spots. It was the map that was probably rotatable or walkable in some way, while the inserted film stills as two dimensional cards modelled in 3D could be viewed from different directions.

This first version of the work was created in Werkleitz Gesellschaft, Germany in 1997-98 in the EMARE scholarship program. On the online interface of the Werkleitz Gesellschaft (Tornitz, D) archive there is no photo or description of it, it is only referred to as a video tape in the archive 30). The equipment Révész had been able to work with there, was not available here even several years later, and it would not be surprising to learn that the institution accepting the exhibition, the Art Gallery in Budapest was not technically prepared to show the interactive version of this piece. The exhibition had an outstandingly high budget at the time31)), however, the number of interactive pieces on show still posed a remarkable challenge in terms of the available technology.

We can learn from the description above that the video and the interactive material interpreted or we can say modelled each other. Both are maps of each other. All this would be in perfect harmony with the author’s description and interpretation, but it was only published in the printed catalogue of the Media Model exhibition, but never on the previously quoted interface.

“The title, as well as the structure of the work, is borrowed from Bridge. San (from the French sans atout) means a play without a trump card. In such cases, it is only the hierarchy that counts; neither colour has the advantage. I used people in place of cards, in an everyday action. Always in pairs - so that the symmetry (of playing cards) would be attained, visibly, to the fullest extent possible. In this case, horizontally, rather than vertically. Between the pairs - i.e., one card - appears the next card, the next pair. This works in such a way that their succession and hierarchy derive from the symmetry of the card itself. When the camera arrives to one of the pairs, their action appears in the centre of the next playing card. This card is perpendicular to the preceding one. And so it proceeds all the way through. In other words, there are two planes in the space, perpendicular to one another. The former is oriented West-East, while the latter is North-South. The shift is continuous, with the camera movement occurring in arcs. What I have now tried to describe in words appears on the wall in the form of a projected video. I called it a map during the course of the work. I placed another map on a monitor, on a table in front of the projected image. This is truly a bird’s-eye view image: the groundplan of the video shoot. I referred to this as a map because I considered this situation as something Vermeeresque. Figures (i.e., we, the viewers) are standing at a table, perhaps even pressing on a mouse. All of this in the expectation that we can bring about some change in the projection (the map). On the wall, there really is a large image, albeit not bird’s-eye view, but nevertheless a map. A two-dimensional map is at the disposal of those standing at the three-dimensional table. There is no window in the room, so that the primary light-source is also this map. The large map “goes on its own”, while the small one only aids in its interpretation.”32)

It also turns out from the quoted text that what we have here does not involve or does not exactly involve the work that you can find on the C3 website, but rather the version that came about at the exhibition in the Art Gallery. The really confusing part here is that the change is not highlighted by being marked with another year or even a subtitle, and certainly the fact that the author equally uses the word “map” for all “projected views”, which is obviously important for the purposes of interpretation. You even have to read the subtle allusions in the text several times before you realize that some kind of a transformation happened here.

The exhibition in Budapest featured only one video on a projector screen, and below that, a little bit farther in space a simplified, two dimensional map on a small computer monitor. 33) It is clearly visible from the pictures documenting the exhibition that this is the picture that you can find on the C3 website under the title Videóarchívum és médiaművészeti gyűjtemény (Video Archive and Media Arts Collection).34) For some reason, the documentation that appears here about the same work is totally different from what is available under the title Media Model exhibition in the C3 database.35) It is probable that this version of the work got into the collection only after the exhibition.

Fig. 7: Révész László László, SAN, 1997-1998, The Art Gallery, Budapest.36)

Fig. 8: Révész László László, SAN, 1997-1998, The Art Gallery, Budapest.37)

Besides the exhibition catalogue, the small computer escaped all other photographers’ and documenters’ attention, the exhibition was even video taped as if the monitor complementing the installation had not been there.38)) It was omitted from the picture, superficial viewers did not realize that it belonged to this work.

Technical difficulties or lack of equipment had presumably led to this solution at the exhibition in the Art Gallery, or at least it seems as if the author had had some justified or unjustified dissatisfaction regarding the situation. The last lines in the catalogue description of the work of art written by Révész may at least seem to refer to that when read from a certain perspective:

The situation would be different if those standing at the table could freely intervene into the sequence of events. But the hand that is dealt (i.e., the hierarchy) has the upper hand: it is from the dealt hand (the situation) that the appropriate play may be made.

Nevertheless, the most relevant question that arises for me here through this example is whether the original files could be found anywhere, in the artist’s own archive or among the files of those who used to work with him at the time. And we would be especially interested to know whether, based on the description and the pictures in the documentation, it would be comparatively easy with today’s technologies to reconstruct the 3D environment that meant an extremely big challenge more than twenty years ago.

Transer

The third and last example concerns what actually happened in practice when a former and in several locations variously documented work was presented again at an exhibition. Loss of memory, as well as negligence on the part of both the author and the institutions played a significant role in the story.

The C3 exhibition in 2001 called Science Fiction, which was not housed by the Art Gallery in Budapest but by several smaller arts institutions, in case of Révész the Trafó Gallery, the artist appeared with the work entitled Transer. At the international exhibition called Both Ways organized by Ludwig Museum as part of the Science in the City festival on the site of Trieste Contemporanea in August 2020 a video called Transfer was on show.

Fig. 9: Révész László László, Transer, 2001. Trieste Contemporanea, Trieste. Photo: Marino Ierman. 39)

In the text of the exhibition guide, the curator, Anna Bálványos characterizes Révész’s work with this sentence: :”… his video Transfer is based on the idea that the movement of the Earth can be used in transport: Lyon and Szekszárd, a city in a wine region in Hungary, are on the same latitude, so wine transportation to Lyon can be easily solved according to that.”40) All other texts published about the exhibition basically quote these summary type sentences word for word, because on the basis of a virtual exhibition published on the site of Trieste Contemporanea, it seems that the video was shown without any further written explanation, although in itself it can hardly be interpreted and is really obscure.

This work features as a video installation or in other places as an interactive installation illustrated by only some video stills in the 2001 C3 exhibition catalogue.41)

We have not found detailed imagery about this exhibition, the curators, Miklós Peternák and József Mélyi unanimously recollect that detailed documentation was probably not even made at all.42) We can say, the arts press reacted in a strange way to this exhibition, just like to the one before this called Media Model. Basically, they gave the impression as if it had not been an arts exhibition. A lot was said about desirable or undesirable receptive-exhibition viewer attitudes in connection with the new genres, interactivity and video gaining ground, the inevitability of new technologies,43) but describing, interpreting works of art almost never happened, they were even mentioned quite rarely.

Fig. 10: Révész László László, Transer, 2001.44)

An information booklet was made for the 2001 Science Fiction series of events, and also a smaller catalogue in connection with the exhibition, the latter including Révész’s interpretation in its entirety, and it turns out that, in fact, we are watching a a filmed report about the scientific works of a fictitious inventor, which was made after the mysterious disappearance of the inventor and in which his disciples half convincingly, half disbelievingly tell about his plan, namely, that he would use the energy of the Earth’s rotation in some obscure way to solve international transportation on the same latitude. Transportation would work with a machinery that he invented. As an explanation for the workings of the machinery, during an experimental journey, due to the sponsorship of a film factory he would document the rotation of the Earth as a photogram made about the stars on a roll of film stretched on the ground on the complete route between Szekszárd and Lyon.

As the closing lines say:

“The main goal of the work is the reconstruction of the researcher's character with all remaining documents. I would like to exhibit all the documents in my possession: the film, the plans, a short section of an interview, and his notes.”45)

Based on this, the film, the notes and the plans may have constituted the rest of the installation. There is a slight uncertainty in the sentence above, which may derive from the practice that in the aforementioned catalogues, in all three exhibition catalogues that are included in the essay the participating artists made each and every description of the works of art. These writings had obviously been made before the opening, since it was important for the organizers to complete the catalogue before the opening of the exhibition to make sure it was readable together with the exhibited pieces, since, as we have already seen it, descriptions may be really important in the interpretation process. This practice had led to the fact that some of the artists did not speak in the third person singular, but spoke their own voices in the descriptions.

Révész plays with this role. He does not introduce himself as an artist, but as a modest researcher and archiver possessing documents about a mysterious researcher. As such, he remarks modestly what he has in his possession and that he would like to show it all. However, since he is playing a role it is not obvious if he really owns the “documents”, he really made these works of art. But at this point the two roles meet and among the lines the artist reveals himself because in the catalogue he reuses the plan of his installation, a proposal. As a result of this nice and witty solution this description also becomes part of the work, in a certain sense. Let me note here that even the work itself deals with the topical questions of documenting, archiving and making collections, among other topics.

Anyway, whether the above documents and the “original” experimental film material had been completed or not, they were not put on show in Trieste, and since the curator had only been able to see the shorter one of the two catalogues46) that did not contain the description in full and the artist had not informed him about that either, he could not find out that the Transer originally was the name of the transporting vehicle that exploited the movement of the Earth. The title of the work of art also comes from this, so it is not Transfer but Transer!

This situation gives rise to numerous questions and one of them is about the case when the video element of a work becomes part of a media arts archive or digital collection what happens to the objects that possibly belong to the work in the installation, they obviously cannot be stored there, and since they cannot be copied they will still remain in the possession of the artist. Hence the archived work of art will necessarily become fragmentary.

The previous three cases deliver several lessons. The primary task, which is already in progress, is definitely to collate all C3 documentation that can be found in different places and to connect it with other archives and institutions concerned. C3 plays an especially crucial role in executing this task, because right now its database in Hungary is unique in the sense that it concerns exhibitions that do not belong only to a single institution like the Art Gallery, but it has extensive information about the works of the previous generation’s most important Hungarian media artists from the beginning.

While regrettable from the point of view of the Révész oeuvre, the main lessons that derive from the situation caused by his death do not involve posterior documentation of this specific oeuvre as the most urgent task to complete.

It is possible, moreover it is necessary, of course, to find the people the artist worked with at the time to use their memories, descriptions or probably objects (documents) until the heritage can be researched again. It is more important, however, to avoid similar situations in the future and ask for the help of contemporary living artists to document their works better. Several aspects emerged in the course of what has been described above, several points of reference that may help define directions and preferences for the work to be done.

The basic question is what we expect of an archive that is meant to document and preserve media art works, the initial history and most significant works of the genre and make them consumable for the next generations to come. In many cases it turns out that even if the works can be preserved in the form of original files, their playback is hindered by more and more obstacles. While continuously converting them to the latest technologies seems to be an uphill struggle, preserving them in their original forms may require operating ever more extended museum equipment.

Still, when an exhibition situation like the one above arises, it turns out that one of the most important bits of information about a work is what should appear and how at an exhibition so that it makes sense and becomes approachable for today’s audience. The archive in its present form, unfortunately, hardly ever provides an answer to this question.

We would deem it good practice if the artists whose works are listed in the archive and who can still be contacted today were asked about what they consider necessary to be included in the introduction of their works. What minimum requirement is needed to make their work appear. We do not mean technology here, but for example in the case of SAN the significance of interactivity, the map view, or how important it is for the projections to appear in the same size. Likewise, in the case of e.g. Transer it would be important to know what belongs closely to this work of art. What texts, possibly objects or presentation-projection methods form a part of it.

Ideally, descriptions like these could also be supplemented by the former exhibition photo documentation. Such images and views or descriptions, in my opinion, would be just as important as the technical requirements of the work, since it is more probable to create the reconstruction with the latest technologies from the view itself rather than reconstructing the former scene and especially the former effect based on only the technical requirements. At this point there is also the concern of how much a kind of a retro feeling proves to be useful or even acceptable, which the appearance of old equipment necessarily bears, in case of works of art that gave a glimpse into a futuristic world at their time.

Home Page: an investigation into preserving the net art collection of C³ Foundation

Why net art?

The C³ collection contains a small but significant selection of net-based works from the early days of Internet art in Hungary and abroad. The majority of the works date from the second half of the 1990s, a period marked by the exploration of the web as a new platform and means of communication. For artists of the time, websites offered a new medium for experimentation, as structure and design principles were not yet set in stone. The artistic freedom to shape the internet motivated many creators to produce exciting and unique work. The C³ collection offers a selection of works, including seminal artists of this period as well as experiments. Preservation efforts, however, tend to be passive, with a lack of resources not allowing for the activation of individual works.

Over the years, many platforms and solutions have become obsolete and unavailable, and some specific examples of preservation efforts will be discussed later. In 2022, with renewed interest in the 1990s and against a backdrop of accelerating digital content production, net art and the artistic values it represents are once again in the spotlight. For decades, the conversation around net art has been stimulated by a number of theorists and organisations (e.g. Variable Media Network, Monoskop, Zentrum für Netzkunst) and conservation work on web-based artworks is being done in different parts of the world (Rhizome, LIMA), but this is not the case in the Central and Eastern European region. This fact was one of the driving forces behind C³'s recently launched Home Page project.

We cannot pass by the debate on the terminology of net art, where a single dot or dash is of great importance for the practices described by the term. The literature distinguishes between a version of 'net art' with a space and 'net.art' with a dot, the latter coming from Vuk Ćosić and denoting the internet activist movement of the same name in the mid-1990s, whose members included Alexei Shulgin and Natalie Bookchin. Therefore, the term 'net.art' is used in the literature and on the Home Page website specifically in relation to this movement, while 'net art' is understood as a much broader category encompassing a wide range of internet-based art practices.47) Various terms are used to categorize artworks on the various C³ platforms, including 'net-art', 'web-based art', 'network art', and 'web project'. Web project generally refers to artworks that are more process-based and constantly changing in nature, but C³ uses the term as an umbrella term for net art. As the collection is currently available on various online platforms (websites), preservation efforts have identified the need for a comprehensive, synthetic summary or presentation that integrates the interdisciplinary nature of the works.

A loose methodology of artistic research was applied in this process.

Net art works and artists at C³

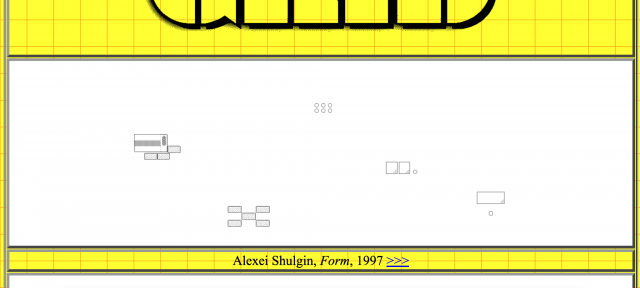

Fig. 11: Alexei Shulgin's Form, 1997, on Home Page, 2022. Source: C3 Foundation.

The net art collection has been created in line with C³'s original aims: to promote and explore the potential of the internet for the general public. There are three categories of net art works in the collection: 1) works created as part of an international residency programme, 2) works created by local artists, and 3) websites that are not created with artistic intent but retain some artistic value (this category includes websites created to document exhibitions, conferences, radio stations, video collections, etc.). As with most early net art works, their interdisciplinary nature makes them difficult to categorise. While Alexei Shulgin's Form (1997) is an example of a classic net art work,48) the same cannot be said of Ctrl-Space (1999) by the Dutch-Belgian artist duo Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans (JoDi). This is listed under web projects on the C³ website, but in reality it is not a net art piece, but a downloadable file which was then uploaded into a computer game called Quake to create a unique gaming environment. Ctrl-Space is described as a network game that can be accessed and played on the internet, but the definition of a network game has changed significantly since 1999 and means something different. Another example of an interdisciplinary net art work is Lapsus Memoriae (2002) by urtica (Violeta Vojvodic + Eduard Balaz), an online memory game.49)

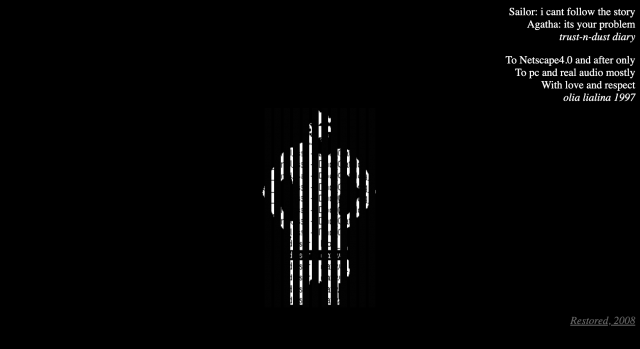

One of the iconic works in the collection is Agatha Appears (1997) by Olia Lialina, which underwent an extensive restoration in 2008.50) By this time, typical conservation problems such as incompatibility with contemporary browsers, loss of interaction element, and damage or loss of certain files had become apparent. As with many early websites, the home page contains instructions for viewing, but these conditions can only be mimicked in an emulated environment.

Fig. 12: Olia Lialina, Agatha Appears, 1997. Source: C3 Foundation.

“To Netscape4.0 and after only

To pc and real audio mostly

With love and respect

olia lialina 1997”

The process, initiated by Elzbieta Wysocka, has set an example for the organisation, but has also demonstrated the effort and expertise required to handle delicate works to the right standard. János Sugár's Dokumentum-modell (1997) was restored for the Ludwig Museum Budapest's 2020 exhibition. Lacking any documentation, the reconstruction relied on the artist's faint recollections, arguably creating a new work based on an old idea. Technological upgrades to the original hosting server meant that all media on the site had to be replaced, including videos from Budapest traffic security cameras from 1987 and the artist's answering machine messages from the early 1990s. Interestingly, during the same exhibition in 2020, Olia Lialina justified her decision not to allow Agatha Appears to be shown by claiming that a simulation of the original hardware and software interface was required to exhibit the work, otherwise it was available online for anyone to view.

As time goes by and internet standards change, more and more works become inaccessible. On the other hand, as the C³ collection shows, accessibility is not enough to preserve a work of art. Without presentation, discussion, the creation and maintenance of networks of care and activation through awareness-raising, works of art will be forgotten. For the Home Page project, our aim was to rescue this moment in time when the web was seen as an artistic medium, surrounded by endless enthusiasm and utopian optimism for the future. Rather than focusing on a single work, we took the collection as a whole and analysed it, looking for specificities in terms of unique language, theoretical charge, activist motivation and communicative innovation. We wanted to create a new body of work in which browsing is dominated by the joy of discovery, as opposed to carefully organised information made available with a single click. The new artwork takes the form of a website, presented as an alternative archive. This is not to disregard conservation perspective, quite the opposite - our aim was to provide an expanded view of conservation in practice and to take advantage of the opportunity provided by the New Media Museum project to bring the essence of early works in the care of C³ to a wider audience.

Home Page, an alternative archive of net art

The works of Márk Fridvalszki deal with the sensual materiality of failed modernist visions. The artist usually employs a variety of media, such as wallpaper, found and manufactured objects, digital printing and other printmaking techniques, and combines them in all-encompassing collages. His artistic programme can be described as archaeo-futurological, which means that he deals with the remnants of forgotten utopias, the cultural sediments of our lost collective future. He was commissioned to make a new work by curator Anna Tüdős, who had worked at C³ for 4 years and knew the collection well.

After defining the main theme, Fridvalszki immediately referred to Ferenc Kömlődi's Cathedral of Light, which became the inspiration and guide for the creation of the website.51) From the beginning, the aim was to revive the visual aspects and logical structures of the net art works of the early 1990s. The creators wanted to avoid nostalgic appropriation and to preserve and present the zeitgeist of the 1990s in Hungary and Central and Eastern Europe, incorporating visual inspirations and texts from that period. At the same time, Home Page uses the retro-futuristic visuality of the 1960s/1970s, with a geometric design and vibrant colours. This work, like Fridvalszki's other works, is a collage where the individual elements have a very important reference value.

Creating the website for the artist was akin to editing a publication, and the curatorial work helped to harmonise the organic integration of text and image. The selection of the featured texts followed preliminary research, which included interviews, research in archives and consultation with scholars.

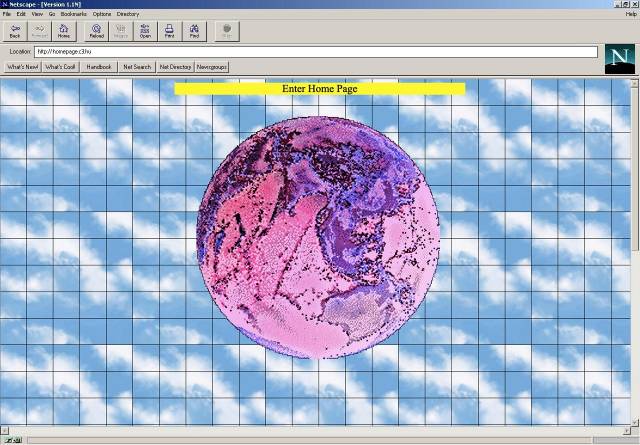

Fig. 13: Home Page in Netscape, one of the most popular browsers of the 1990s. Graphics and concept by Márk Fridvalszki. Source: C3 Foundation.

The site starts with a rotating globe, which suggests the idea of the internet as a way to connect the world. These pre-pages were also a common feature of early websites, usually containing information or a simple 'Enter' button to give the underlying webpage some time to load. After entering, visitors are faced with the main menu. In structuring the menu items, we were careful to ensure that they were poetic but informative, that the topics were distinguishable even if related (e.g. there are links between the 'Cyberspace' and 'Grid' pages, but their focus is noticeably different), and that the dual–local and universal–references of the project worked well together. A good example of this is when a timeline is superimposed over the dot-com balloon graph to give a sense of the interplay between the Hungarian and wider context, and that Hungary was indeed relatively early in terms of internet access and net art.

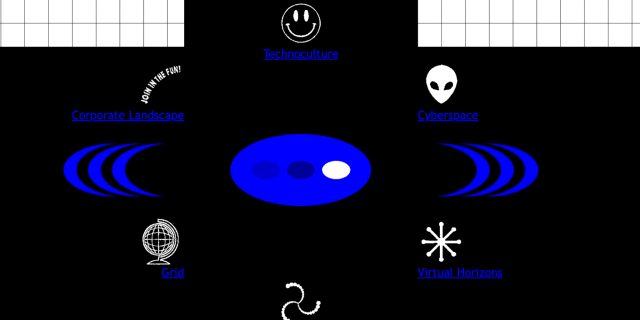

Fig. 14: Home Page, www.homepage.C3.hu. Source: C3 Foundation.

Under ‘Technoculture’, an interdisciplinary understanding of the word is demonstrated:

“The definition of technoculture goes beyond music, literature, film, video, visual arts and all other new forms of artistic expression. It describes a sense of a changed world.”52)

Under 'Corporate Landscape', we reflect on the critical internet culture, and mark the anti-consumerist attitudes, the social distance and loneliness created by technology, but also historical milestones such as the dot-com bubble. Here, Ferenc Kömlődi's words coincide with Geert Lovink's vision of the Internet as a self-generative tool capable of bringing together critics, social movements, NGOs and others.53)

The section 'Cyberspace' explores twisted identities and realities created by online environments, linking the then new concept of cyberspace with a selection of artworks. Similarly, 'Grid' explores the drastically new ways in which information was organized online. Many artists have drawn inspiration from the abstract, mathematical, simple yet informative grids that began to define digital life in the 1990s. The works of Balázs Beöthy, Gyula Várnai and Hajnal Németh are displayed alongside those of Alexei Shulgin. 'Hyperdimension' functions almost as an audiovisual artwork in itself, with music composed by Elod Janky and a narrative scrolling structure reminiscent of the strategies of early net art artists.

Last but not least, 'Virtual Horizons' contains most of the local knowledge and archival data that could be useful for future researchers. In this section, the website details how the World Wide Web was introduced in Hungary in the 1990s, why artists and students took up the medium, and how some of the first few websites were created. It goes into more detail about the history of the World Wide Web and explains how it is truly considered the most democratic medium.

Preservation approach

If one can't update a database (of net art), the right solution is not to create a new one, bypassing the problem. Software-based artworks are constantly changing, so their preservation needs to be flexible. Any presentation of them can be interpreted as a re-enactment, with the original ideas at the heart, but never quite identical to the original. Some artists argue the need to present works using original software, hardware and physical environment (Olia Lialina), others allow the work to transform over time (János Sugár). The exhibition Seeing Double: Emulation in Theory and Practice at the Guggeinheim Museum (2004) presented these two approaches side by side, pairing works of art made in endangered media with their re-created counterparts in newer media.54) In the case of Home Page, a new work was created based on the complex whole of the net art collection with the aim of adding new value. Perhaps Home Page does not preserve the works in the net art collection in the form in which they were once available, but rather fits into a new wave of preservation paradigms that emphasize the importance of systematic presentation, the importance of curatorial choices to preserve the essence of the works, and the inclusion of different actors and disciplines in the 'networks of care' surrounding the works.

The post-custodial paradigm calls for a re-contextualization of archives to seek knowledge and understanding rather than mere documentation and control.55) In archives following this model, as in C³, ownership rights may not necessarily be held by the institution but by individuals. Archivists take on the role of arranging records in relation to other records in the archive or even in other archives, working with others towards the same or similar ends, creating new records and contextualising content along the way. This represents a clear shift from traditional archival practice, where responsibility is more concentrated and power relations more fixed. This paradigm implies dynamic boundaries within archives and between archives, creators, subjects and users. Although usually associated with participatory archival models, in this case it was useful to think about it in the context of the C³ catalogue and preservation efforts, where rather than focusing on a single work, the emphasis was on mapping the dynamic legacy and context of the net art collection.56) The Home Page follows the paradigm in its attempt to recontextualize the collection within the “larger historical and social landscape.”57) around them.

On Home Page, net art works, physical artworks, video art, a documentary, quotes and screenshots contribute to the interpretation of the nineties' mindset, digital culture, utopian or sometimes apocalyptic visions. That “software is stuff unlike any other” and “cyberspace is unlike any physical space.”58) It was important to include 'broken artworks' on the site, such as Szilvia Seres' Culture is Consumer Goods (1999), of which we have a description and screenshots, while the original files have been lost. The inspiration came from Gallery 404, a website set up to challenge the phrase “the internet never forgets,” showcasing the early 1990s net art generations' “attempt to plant a cultural stake in cyberspace” through the display of broken artworks.59)

Future Prospects

The actual home page of C³ is a net art work by Balázs Beöthy, which refers to the periodic table and the unity of science and art.60) The site was created in 1997 and has seen only minor changes since then.61) To many, it looks old and dusty, a relic from the past in urgent need of updating. For some, however, it is an imprint of another era, when faith in technological advances was stronger and the power of experimentation prevailed over economic imperative, and is therefore unlikely ever to change. The website presents all relevant information, although navigation can be an unusual experience.

Net art requires conservation practices that view artworks not as fixed but as a process, “an assemblage that can mutate over time and according to context.”62) On the other hand, many institutions and caretakers are not able to regularly update and transform their artworks. Experimental efforts such as Home Page can provide fresh perspectives in such situations, spark debate and activate care networks. Jon Ippolito stated that “almost every time when you preserve works of new media, it takes a lot of money, it takes a lot of effort. […] But on the other hand, if you look at early games, they have been preserved not by museums, not by curators, not by conservators, but by game enthusiasts and no one gave them a huge grant. They are preserved because they have a fan base.”63) If enough people are enthusiastic enough about these works, or if enough excitement can be generated around them, then we will be closer to being able to preserve them.

Flóra Barkóczi uses Bourriaud's term 'dee-jaying' to describe the creative process that results in Home Page, where the artist creates a work by reorganising or re-contextualising existing artistic practices.64) By presenting fragments of early net art culture in context, using them almost as raw material rather than archival relics, the result is a kind of remix that questions the legacy of this culture and makes connections with contemporary artworks. Home Page remains an open platform with the potential for expansion. All aspiring DJs are welcome to create a new remix.

Part of this essay was translated from Hungarian by Zsuzsa Feladó.

See also the video presentation by Anna Tüdős and Márta Czene in this volume.